Demand has never been greater for the monitoring of objects in orbit and the coordination of their safe movement.

The number of active satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) has surged from less than a thousand in 2019, when SpaceX began launching its colossal Starlink broadband constellation, to more than 10,000 today.

As other megaconstellations join the fray, some forecast that number to reach at least 70,000 by 2030, further straining how Earth’s orbit is monitored and managed.

What’s emerged so far is a crowded, fragmented market of space domain awareness (SDA) platforms built on different sensors, catalogs and analytics. The result: overlapping data streams and inconsistent alerts that risk confusing operators rather than clarifying decisions.

“The problem the operators are facing is that now there is almost too much information, and they don’t know what to do with it,” said Joe Chan, chairman of the Space Data Association, a nonprofit group of satellite operators that runs an information-sharing platform.

“They are getting alerts from many sources, and there is uncertainty of what to do with it.”

Rather than another proprietary map, space trackers increasingly see the way forward as some kind of air traffic control for space, built on shared data standards, interoperable systems and federated networks that would respect national sovereignty while enabling real-time coordination.

The scale of the problem

U.S.-based SpaceX operates the vast majority of satellites in LEO today for its Starlink broadband service.

However, almost half of the satellites set to be orbiting Earth at the end of the decade will be operated by U.S. adversaries — primarily China, according to Tony Frazier, CEO of California-based space-tracker LeoLabs.

“This rapid growth, coupled with the advancement of counterspace capabilities, means space is a contested domain where strategic competition is intensifying,” Frazier said. “In this dynamic environment, the markets for SDA and [space traffic management] services are expanding and evolving.”

The U.S. government’s Golden Dome missile defense program and Traffic Coordination System for Space (TraCSS) initiative are adding momentum to efforts to keep better tabs on orbit, Frazier added.

“Governments are actively trying to get to a point where they can manage SDA like air traffic control,” said Diana Klochkova, chief marketing officer at Privateer, which like others provides free tools for visualizing and understanding orbital data alongside a commercial analytics business that fuses information from space, air, land and sea.

However, “progress has been slow, and the need is immediate,” she continued. “In the meantime, commercial players have to fill that gap.”

A multitude of ventures have emerged in recent years to address that gap, ranging from companies operating niche sensors to others pooling the data that’s available to them, typically leveraging artificial intelligence to model increasingly complex orbits.

Wide, lower-fidelity telescope networks are great for broad coverage, Klochkova noted, while high-fidelity ground radar is better suited for precision tracking. A newer class of satellite operators, meanwhile, is using ultra-detailed on-orbit imaging to gain deeper insight into specific assets.

“These capabilities support everything from observation planning for astronomers to reconnaissance for [Rendezvous and Proximity Operations and] space junk clean-up,” Klochkova added, but “no single company covers it all.”

A proliferation of increasingly diverse approaches is a pattern that has cycled through the industry for decades, according to satellite analyst Armand Musey, founder of advisory firm Summit Ridge Group.

“Some new, higher-resolution/improved sensor will massively expand the market next year [but] when that doesn’t happen, they retreat and focus on analytics,” he said.

“Then the cycle repeats itself. The industry is slowly growing but has not found the ‘killer app’ yet. The same ideas from 25-30 years ago are still recycled today.”

While Klochkova said the market will continue to grow as space operations expand, she acknowledged it may not be enough to sustain every platform now competing for a foothold.

“The market will have to consolidate as roles and specializations shake out,” she said.

Clouding the picture

To help solve these problems, SDA’s Chan called for greater consistency and coordination across the industry so operators can make clearer and more timely decisions.

The Space Data Association, he said, aims to play a neutral role, acting as a trusted hub for data sharing and coordination. Because the association is a nonprofit, Chan suggested that it could offer a non-competitive way for operators to share their data.

Without that, he warned, conflicting rules and fragmented systems will only make space traffic harder to manage in the future.

Commercial analytics providers also see themselves as an essential component to bringing order to this growing complexity.

Comspoc, one of the earliest private sector entrants in space situational awareness (SSA), is positioning itself as an analytic foundation that others can build upon.

Comspoc’s Mission Awareness platform aims to give operators a single workspace for threat assessment, interference prediction and maneuver planning, relying on continuous, physics-based estimation rather than static snapshots.

“Not all data providers are the same, and depending on the situation, one type may be more effective than another,” said Jim Cooper, Comspoc’s lead for SSA solutions. “That’s why collaboration is so important.”

He sees the industry naturally segmenting into three groups: data providers, processors such as Comspoc that offer analytic software and the operational providers that direct monitoring or alert services.

“All these segments function together, and when they do, the commercial community as a whole brings tremendous capability to the market,” he said. “There is room for multiple companies and platforms to thrive long-term — each contributing something distinct to a stronger, more resilient ecosystem.”

Building bridges, not silos

The spirit of collaboration is echoed across the market. Lisbon-based Neuraspace is positioning itself as an orchestrator across data ingestion to operational decision support.

“The SDA ecosystem is inherently interdependent,” Neuraspace CEO Chiara Manfletti said.

“No single actor controls or will control the full chain from observation to maneuver execution. Even vertically integrated players depend on external catalogs or [Application Programming Interfaces (API)]. And there are other considerations as well, such as sovereignty.”

According to Manfletti, the future of the market will depend more on interoperability than dominance.

“The long-term structure may consist of federated, interoperable SDA nodes, each operating under a sovereignty-preserving framework,” she continued.

“Competitive advantage will shift toward firms that can bridge — not dominate — the data ecosystem.”

Neuraspace’s platform uses an AI-native, API-based architecture to automate conjunction assessments, plan maneuvers and report risks directly into operator workflows.

Manfletti said this approach ensures secure governance and sharing across multinational sensor networks, while protecting sensitive data — an increasingly important factor as governments link SDA to national security and defense decision-making.

More join the fray

Newer entrants are leaning into that integrator role. Paris-based Ecosmic says it focuses on turning disparate observations into faster, more usable warnings, rather than building its own sensors.

Similar to others focusing on extracting insights rather than collecting data, Ecosmic fuses radar, optical, passive radio frequency (RF) and space-based inputs from multiple partners to create a unified picture of the orbital environment.

An incoming industry shake-out will depend on who can turn data into insight, Ecosmic co-founder Imane Marouf said.

“The value lies in insight and in the ability to react to threats in the most informed and responsive way,” she said.

“Public and private actors have been investing in sensor networks for decades, but this approach is inherently neither scalable nor resilient.

“With more ground sensors coming online and the rise of space-based surveillance, space data is becoming commodified. At Ecosmic, we are building the infrastructure to host and ingest all of this data, focusing on getting the best view from space and fusing everyone’s data to deliver the most up-to-date and rapid insights.”

The tech ahead

Many space trackers say the next phase of SDA will depend on how effectively companies can integrate diverse data streams — radar, optical, RF and on-orbit — into unified, AI-powered systems.

“Software platforms need to evolve to fuse these diverse data streams in real time, enabling autonomous monitoring, predictive analytics and faster decision-making,” Ecosmic’s Marouf said.

“These capabilities are opening the door to a future where satellites can better understand their surroundings, respond to threats proactively and collaborate more effectively with other assets in orbit.”

Spanish technology provider GMV is in the middle of upgrading the Space Data Association’s orbital traffic coordination platform to better handle increasingly congested orbits.

Under a contract announced in September, the new system aims to integrate multiple data sources and fuse them into unified conjunction messages to reduce alert fatigue and establish more consistent operational standards across operators and governments.

LeoLabs’ Frazier also pointed to how the company uses the latest AI and machine learning breakthroughs to “evaluate which objects merit higher priority for observation and to detect and characterize maneuvers within hours — tasks that historically took days.”

What comes next

As more companies build orbital catalogs and claim the most accurate picture of space, the question is shifting from who tracks the most objects to what kind of mapping truly matters in a market edging toward consolidation.

For Kayhan’s Feyzi: “It really depends on what we mean by ‘mapping space.’ If it’s just about creating a visual catalog and plotting dots on a globe, that’s not particularly valuable — no one truly benefits from that alone.

“But if we’re talking about tracking objects with precision, that’s a much more complex and meaningful challenge.”

Even as companies race to collect ever-greater volumes of orbital data, industry leaders say success will hinge on how effectively those observations are combined and applied.

In the long term, Feyzi argues, the sector must move away from isolated, proprietary systems toward shared, observation-based models that merge data across networks.

“Ultimately, the future of space mapping isn’t about competing catalogs,” he said, “it’s about collaboration and data fusion to create a better, unified understanding of what’s happening in orbit.”

While many space tracking newcomers rely on shared data and open networks, others are doubling down on controlling the sensors watching the skies, or deliberately avoiding them altogether.

For example, LeoLabs operates a global network of radars capable of persistently tracking objects as small as 10 centimeters in low Earth orbit (LEO). The company reports that 90% of payloads in its catalog have a revisit rate of at least five times per day, with high-interest objects revisited up to 13 times daily. It claims 99.3% coverage of the U.S. public LEO catalog, including 99.96% of all payloads.

ExoAnalytic Solutions, which also operates one of the world’s largest networks of optical telescopes for tracking space, focuses on medium Earth orbit and higher. These regions are less densely populated than LEO but still critical for communications and defense.

Meanwhile, Kratos Space focuses on passive RF collection from a network of ground sensors that monitor the signals satellites send during routine operations.

Collecting radio signals to gain intelligence about a transmitter has been done since the advent of the radio, Kratos officials noted, but the strategy is gaining significant traction for commercial space domain awareness applications.

The company has deployed more than 190 RF sensors worldwide over the past decade that can detect, measure and characterize over 150,000 unique signals each day. With RF sensing immune to weather and sunlight interference, Kratos sees its technology as an indispensable complement to radar and optical systems.

On the flip side, companies such as Kayhan Space argue that steering clear of owning or operating sensors gives them an advantage.

“That decision was intentional and is one of our key strengths,” Kayhan co-founder and chief technology officer Araz Feyzi said. “By remaining sensor-agnostic, we can ingest data from multiple independent sources instead of being limited to a single system’s capabilities.”

Kayhan’s Satcat platform unites flight dynamics, conjunction analysis and coordination workflows under one roof. Feyzi said the company generates synthetic covariance for U.S. Space Force catalog data, enriches it with tens of thousands of operator-shared ephemerides and also taps partner sensors to fill observational gaps.

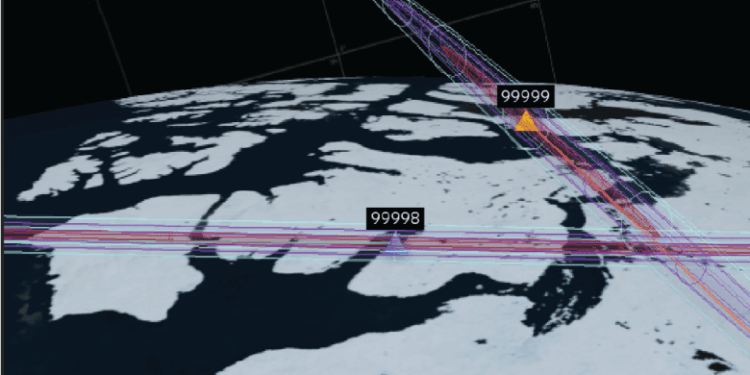

<em>This article first appeared in the November 2025 issue of SpaceNews Magazine, with the title “Space mapping’s proliferation challenge.” That version of the article contained an error that has been corrected here: The print version inaccurately said that the close conjunction between two space objects tracked by LeoLabs (see above image) occurred in 2025. It actually occurred in 2024.