The moon is about to become the first extraterrestrial mining frontier, and most investors may be backing the wrong players. While venture capital pours into space startups promising to revolutionize lunar resource extraction, the real winners may well be companies that have spent 150 years turning rock into revenue: Rio Tinto, BHP, Glencore and their peers.

As CEO of Forbes-Space, a mission partnership and growth services agency working with space companies globally, I’ve advised both emerging space ventures and established industrial players on space market entry strategies. A mining executive asked me last month whether his company should invest in lunar resource extraction. Here’s why that matters — and what you need to do about it.

Lunar economics don’t fit the VC playbook

The space mining market, projected to reach $20 billion by 2035, represents enormous opportunity. What the growth projections don’t tell you is that space mining is much more than just a technology challenge, it’s a massive capital deployment challenge that dwarfs most startup funding cycles.

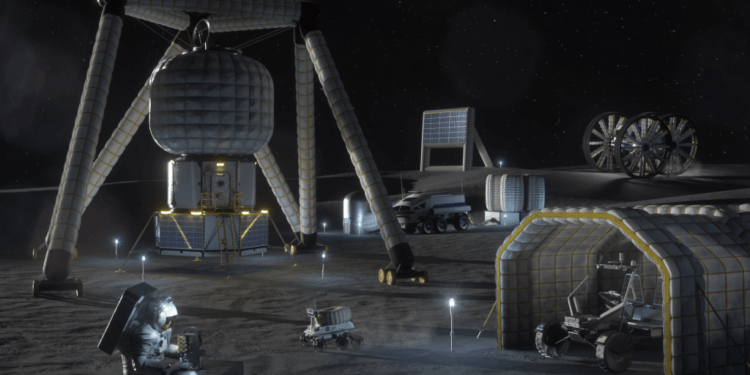

NASA’s Artemis program is driving a race to establish permanent lunar presence. The prize: water ice in permanently shadowed craters at the south pole, regolith for construction and potentially helium-3 for future fusion applications. Multiple commercial landers reached the surface in 2025 — some successfully, others less so, but the infrastructure is coming faster than most here on Earth outside the space industry realize.

After speaking with several lunar experts, it seems extracting lunar water ice profitably requires deploying at least 20 tons of mining equipment to the surface. Even with SpaceX’s Starship potentially dropping costs to $10 million per ton (a best-case internal cost estimate, not a customer price), you’re looking at $200 million just for equipment delivery.

Traditional mining companies routinely deploy this kind of capital with decade-plus payback horizons. They understand patient capital. Venture capitalists need exits within five to seven years. That timeline doesn’t even cover the development phase for lunar mining operations, much less generate returns.

The expertise gap nobody wants to admit

Walk through Rio Tinto’s autonomous operations in the Pilbara, and you’re seeing the future of lunar mining. Remote operators control 200-ton trucks from Perth, 1,500 kilometres away. AI optimizes drill patterns. Robotic systems handle materials in environments humans rarely enter. They’ve perfected this over two decades.

Lunar mining is fundamentally a resource extraction problem that happens to occur on the moon. Space startups excel at getting there. But once you land, the hard part is mining — and that’s where most space companies have zero experience.

Why the moon beats asteroids

Another point to note is that asteroids often dominate headlines with their theoretical mineral wealth. But lunar mining will lead the first wave for three reasons:

Proximity. The moon is three days away. Near-Earth asteroids require months-long transits with limited windows. When equipment fails — and it will — the moon allows faster response.

Infrastructure. NASA and international partners are building it now: landers, communications, power systems. Asteroid mining starts from zero.

Markets. Lunar mining will benefit other space operations well before it benefits anyone on Earth. Water ice converts to rocket propellant for Mars missions and deep space exploration. The customer base exists and has government backing. Asteroid mining must create its market from scratch.

Asteroids will matter eventually. But the path runs through the moon, giving early lunar operators massive advantages when asteroid mining becomes viable.

What you must do now

This isn’t about watching history unfold. It’s about positioning before the window closes. Here’s what each stakeholder needs to do immediately:

Investors: Start tracking traditional mining companies’ space investments — robotics partnerships, autonomous systems R&D, space logistics stakes. These quiet moves matter more than flashy announcements. The winning investments will be mining companies buying space capabilities, not space companies learning to mine.

Space company executives: You’re not competing with mining companies — you’re their potential acquisition or partnership target. Focus exclusively on space-specific problems: lunar access, environmental survival, spacecraft operations. Find mining partners now. Build relationships at industry conferences. Learn their language. Your exit strategy depends on becoming indispensable to companies with capital and extraction expertise.

Mining executives: Your five-year window is already closing. First movers will shape regulations that govern this industry for decades. Start building partnerships with space logistics providers this quarter, not when infrastructure matures. Hire aerospace engineers. Establish a space focused division. Your competitors are already moving.

Policy makers: Clear property rights and resource ownership frameworks will determine which nations capture value. The Artemis Accords provide foundation, but domestic legislation defining resource rights is urgent. Ambiguity helps no one and favours international competitors with clearer frameworks.

Advice for would-be lunar miners

Traditional mining companies survived commodity crashes, national conflict, regulatory complexity and technological upheavals for over a century. They deploy massive capital across decades. They turn raw materials into profitable products at industrial scale.

Space startups bring innovation and speed. But they’re trying to master two incredibly complex problems simultaneously — space operations and industrial-scale extraction.

The winning formula isn’t mysterious: partnerships combining mining expertise with space access. Companies building those bridges now will dominate the first extraterrestrial economy.

So, here’s my challenge if you’re connected with the lunar economy: What are you doing this week to position yourself for lunar mining? Not when the market matures; this week.

The space mining revolution is coming, but it won’t look like the investment community expects. It will be led by companies that understand both space above and the ground beneath our feet. The future belongs to those who can bridge both worlds.

<em>Stirling Forbes is CEO of Forbes-Space, the space trade consulate of Europe and a global mission partnership and growth services agency. He holds an MSc in Space Studies from the International Space University and has written extensively on space industry commercialization.

SpaceNews is committed to publishing our community’s diverse perspectives. Whether you’re an academic, executive, engineer or even just a concerned citizen of the cosmos, send your arguments and viewpoints to opinion@spacenews.com to be considered for publication online or in our next magazine. The perspectives shared in these opinion articles are solely those of the authors.